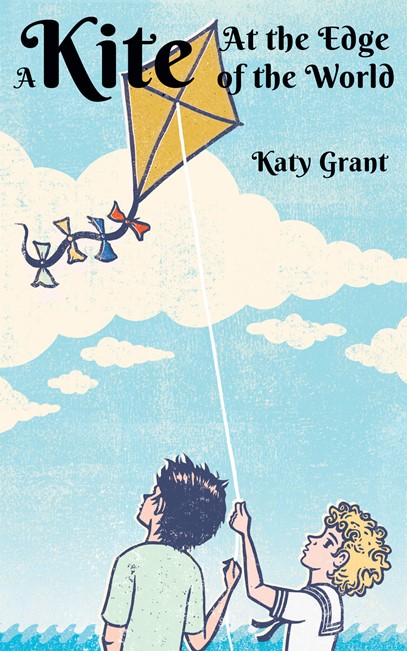

A Kite at the Edge of the World

“The book asks some big questions about life, death and memory… A poignant, elegant story about loss and the enduring power of love.” ~ Kirkus Reviews

It had been a great day. Perhaps the Best Day…

A seaside village many years ago. A boy makes a new friend who says he has always wanted to come to the seashore. This is his last wish, to see where the world ends and the blue begins—because he is dying.

“Then we should do something fun today,” the younger boy announces. Fun! With all the doctors and hospitals, there’s been little time for fun. But what should they do?

Flying a kite is great fun on a windy day. But first they must make their kite. And they’ll need supplies. And the money to buy them. And they will have to get around all the grown-ups who might stand in their way.

And so this never-to-be-forgotten day begins. This is a story of friendship. Of first loss. And of seizing the day.

Chapter 1

I am an old man nearing the end of my life and not the least bit sad about it. Now that my days are numbered, I realize I have spent my life, not lived it.

I am alone now. My wife dead, my children grown. It’s a solitary existence but not an unhappy one. I walk to the park and sit on a bench when the weather is fine. When the weather is poor, I stay inside my small rooms and brew a cup of tea.

Now that my days are numbered…. Come to think of it, my days have always been numbered. Whether one has been granted a long or a short life, it is possible to count the days in a lifetime. I have been given thirty thousand days—and then some. But as waves of memory long buried wash over me, I find myself coming back, again and again, to one particular day.

A great day. Perhaps my best day.

A day when I met a new friend. A day when I stood at the edge of the world and flew a kite.

Chapter 2

Each year when I was a boy, we would go to the seashore on holiday. I can see the village now. Rows of little wooden cottages painted white with roofs of red shingles. A great many wooden boardwalks. The lovely thumping sound they made under bare feet—despite the very real danger of splinters. Along the boardwalks, decks with wooden chairs, also white. Tables shaded by blue striped umbrellas. An occasional gazebo.

But mostly sea and sky and sand. The turquoise sea, the azure sky, the buff sand. The salty taste of the breeze. And the smell of fish, not unpleasant in the sea air. Dots of white on the ocean where the waves peaked. The sky—a blue suffused with sunlight—expansive, endless. Sands glittering white at noon, tawny at sunset, shape shifting. Sea and sky and sand all meeting at the confluence of that little white seaside village.

A village peopled mostly with women and children. Men were less present. They went back and forth between their work in the city and their families on holiday at the shore.

On one particular holiday, I had seen a boy for several days, walking with a plump old woman with gray hair wearing a wide-brimmed straw hat.

Sometimes I’d see him with a pretty woman, younger than the plump one, with stylish clothes and hats that looked like they belonged in a fancy restaurant rather than at the seashore.

I had always avoided the other kids whose families were staying in nearby cottages. They were noisy and boisterous and sure of themselves. But this boy was different.

He seemed older. Something about the way he walked. He never played or skipped or ran about. He’d just walk beside the old woman, or the younger one. Always with his hands clasped behind his back. I started keeping an eye out for him, looking for him whenever I was out.

My mother and nurse were busy with my sister, the baby. So I was allowed to play along the seashore with my blue metal pail and red shovel, to look for seashells, or to catch the little crabs scuttering sideways across the sand.

One gray, breezy morning I’d walked up the shoreline because I could see a lone figure standing on a rocky ledge overlooking the sea. Up the shore past the little white cottages of the village, the beach narrowed into a thin strip that soon disappeared, giving way to piles of rocks. Above the rocks, the land jutted out over the crashing waves below.

At first, the figure was too far away for me to recognize. I kept walking, carrying my blue pail in one hand, the red shovel knocking about and making a metallic clink with every clumsy step I took through the deep sand. The wind tossed up sprays of fine grains in my eyes, but I squinted and kept going. As I drew closer, I could see it was the boy. He was alone.

Chapter 3

I’d now reached the rocky point of the beach. Up above me stood the boy. He must have seen me from up there. I dropped my pail and shovel in the sand and began climbing the steep hillside. I had to use my hands to grab onto the wet rocks above me, and their slick, jagged edges pressed against my bare feet. After some time and a lot of hard work, I made it to the top.

I stopped to catch my breath. The boy stood facing the sea, but he had turned his head to look at me.

“Quite a climb,” he said.

“Yes.” I still puffed in and out, filling up my lungs with salt air.

He was wearing a pale green shirt, the color of cool sherbet, and cream-colored long pants rolled up to reveal bare feet. In one hand, he held a pair of canvas slippers. His hair was straight and dark, parted on one side. The breeze blew strands of it into his eyes.

I envied him his straight hair. My hair was a tangle of blonde curls. Often I would pull and tug at them, trying to straighten them, but it never worked. I had begged my mother to cut my hair short, but she would only smile and run her hand through those awful curls. And not cut them.

I also envied his long pants. At the seashore, I always wore either white or navy sailor suits. Today, I was dressed in a navy one.

“I’ve seen you,” he said. “I see you walking on the beach and digging in the sand.”

I nodded. I was still so out of breath it was hard for me to speak. The boy turned back to face the sea. Now that we were together, I was sure he was two, maybe three years older than I was. He was standing near the edge of the cliff, so near that it gave me a fluttering, uneasy feeling in my stomach. I was careful to stay back a safe distance, on solid ground.

Thick, heavy clouds made the seashore look like a strange new world. Their layers covered the sky like a blanket. Strong winds sent these dark folds sailing across the sky. The whole world seemed changed and unfamiliar in this gray light.

“This is just as I always imagined it.” He stood with his back to me. “I’ve wanted to come here for so long. And this spot here—this is just as I thought it would be.”

“You’ve never been to the seashore before?” I asked. We had to speak up against the roaring sea below us. The wind stirred up whitecaps in the green waves.

“No, never. We live so far away, it’s not convenient to come. But I have a map at home in my room, and I’ve always looked at all the blue and asked my mother and father to take me to the place where the world ends and the blue begins.” Then he turned to face me. “My name is Ilio.”

Ilio—I’d never heard anyone called that before. But I didn’t say anything about his strange name. I told him mine.

“You’ve been here before?”

“Oh, yes. We always come here,” I told him. “We come every year.”

“Lucky!” He tilted his head to brush away the strand of dark hair the wind kept whipping into his eyes. “I love it here. I feel like I could fly out over the blue water and up, up, up—into forever.” He stretched his arms out above his head, and my stomach did a somersault. I felt like I should grab him by the back of his shirt and pull him towards me.

“After I leave, I’ll not see this place again. But at least I could come here once. I always knew from looking at the map what a sight this must be. It was my last wish—to stand at the edge of the world.”

“Last wish?” I asked.

“Yes. My father said he would give me anything I wanted. Because I’m dying.”

He didn’t sound sad when he said that. It was almost like I’d asked him the time and he’d told me.

“You’re dying?”

His shoulders shrugged, and he clasped his hands behind his back. “Yes. Some terrible illness. Incurable. No hope—all that. They’ve tried everything—doctors and hospitals. I guess I should be angry or frightened . . . or . . . I don’t know what. But . . . it’s just the way it is.”

Even though his back was turned, I nodded, accepting his explanation without any questions. Neither one of us spoke until I broke the silence. “Then we should do something fun today.”

Ilio spun around to face me. “What’d you say?”

“I think we should do something fun today,” I repeated, more strongly than before.

He smiled at me, showing a flash of white teeth. He took two steps forward. I was relieved he wasn’t so close to the edge now. I felt better that he was on solid ground.

“No one—no one—has ever said that to me before. Ever! We’ll be great friends, you and me! What fun things are there to do?”

I basked in the light of that smile. Great friends. I liked the sound of that. I tried not to show how happy it made me feel.

“Oh, there’s lots to do! We could hunt for crabs on the rocks, dig for clams. Look for seashells or build sandcastles. I have a ball in my cottage. I’ll run get it and we can play in the waves.” Then I remembered I wasn’t allowed in the water unless my mother or nurse was there to watch me.

Ilio shook his head and looked down the beach in the direction I’d come. “Not today. It’s cloudy, and there’s so much wind. The water is too chilly. See—there’s no one out there at all today.”

It was true. The weather was cool this morning, so the seashore was deserted. Small groups of ladies and a few men would stroll into the village and stop at the little cafés with wrought-iron chairs and tables on their covered patios. The ladies would eat dainty sandwiches and pastries and drink hot tea, and their husbands would order beer or a cold lemonade while they smoked their cigars and talked about how the sea air was much better than the stifling city.

“Well, since it is so windy, we could fly a kite.”

“A kite?” Ilio tilted his head as he looked at me. “Do you have a kite?”

“No, but I do have a book. It shows how to make one. It has all the directions. It looks easy—I think.” The words rushed out of me all at once.

This book had been a birthday present. It was filled with pages of riddles and puzzles and crafts. There were small boats to make out of bars of soap with pencil masts and paper sails. There were directions for pinwheels, and telephones made with two paper cups tied together by a long string, and invisible ink from the juice of a lemon, and mosaics of artwork out of bits of crayons melted between two sheets of waxed paper.

I loved looking at all these pages with illustrations and instructions. But I’d never made anything at all. I’d asked my father to help me, but he was busy with work, and Mother was busy with my baby sister, and Nurse was cross because of the corns on her feet.

“Let’s get it then! Come on!” Ilio scrambled down the hill to the sandy beach below. I scooted down after him. He’d already snatched up my pail and shovel and was stumbling through the deep sand, carrying his shoes in his other hand.

A few months before I began working on this book, I happened to re-read The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery. My sister Nan had loved The Little Prince, and she’d encouraged me to read it when I was about nine or ten. Re-reading it as an adult after so many years was a revelation. I now saw this story on a completely different level than I had when I first read it.

That experience got me to thinking. I wanted to write a book that could be read by both children and adults. So I started to think about what story I wanted to tell.

Around that same time, I had three different friends deeply affected by grief. Each had experienced the death of a loved one. I felt completely helpless as I listened to them talk about their loss. I didn’t know what I could say to ease the pain they felt.

So I decided to wrestle with the topic of death and grief and loss. I thought about how even after someone you love has died, that love doesn’t end.

Gradually, this story formed in my head. I liked the idea of focusing on a single day when the bond between two new friends would be sealed forever. They should do something fun. When I had the idea of them trying to make a kite together and then fly it, the story began taking shape.

Of all the books I have written, this one is the least autobiographical. But the old man telling the story about himself as a boy and his new friend Ilio—they became very real to me. So did the little seaside village. It began to seem as though I had been there. And that I had known these characters all my life.